Leah Hadfield’s “why not me?” moment arrived last fall, about nine weeks before November’s election.

The 36-year-old single mom had toyed with the idea of running for City Council in her hometown of Roslyn, a former mining community near Cle Elum that was governed entirely by men.

In September, she launched a write-in campaign against two male candidates, including an incumbent who later withdrew from the race.

“It kind of felt enough like the right time,’’ said Hadfield, who works as a barista at a local cafe and general store.

She won by 15 points, and last Tuesday took her seat on the council, one of two women elected to the Roslyn council in November.

Hadfield was at a loss to explain her victory, but she suspects voters were looking for a woman’s perspective and new ideas for protecting the quality of life in Roslyn, population about 900.

“There’s a vast amount of divisiveness in politics, and there could be a feeling that maybe women are better at bringing people together,’’ she said.

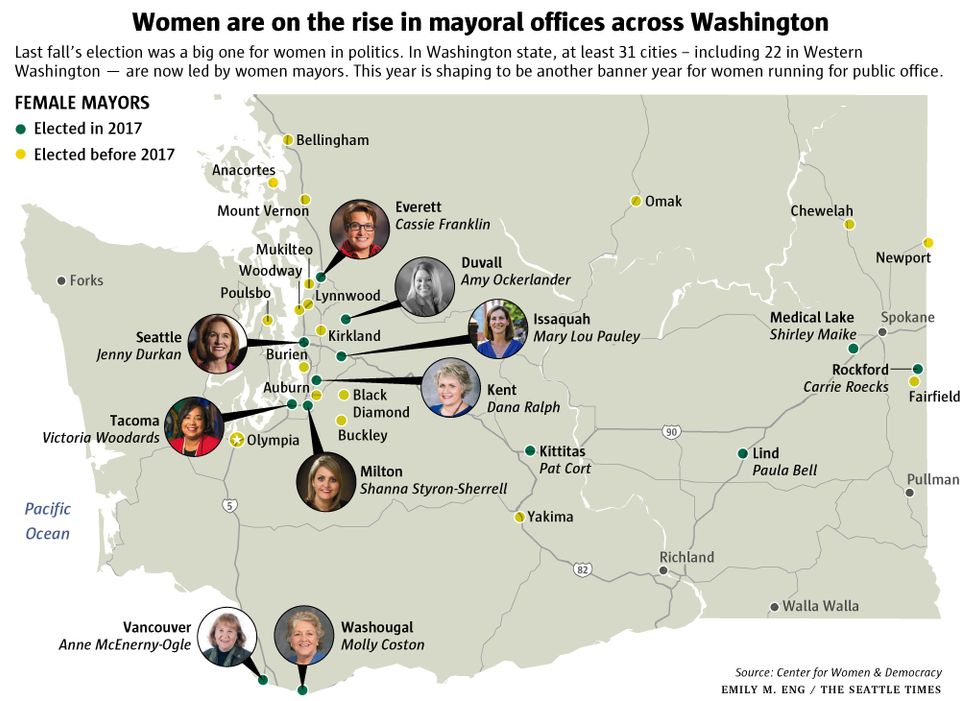

Whatever the reason, Hadfield was among an unprecedented number of women elected to office in 2017, many of them drawn into the political arena by Donald Trump’s presidency.

This year is shaping up as a banner political season as well, with thousands of women lining up to run nationally, including at least 79 for governorships in 31 states.

Where once there was a dearth of women in public office, there is now a slew of women challengers and a backbench of women office holders in executive and legislative posts positioned for higher offices, said political consultant Cathy Allen, president of The Connections Group in Seattle.

“We’re not ‘the first’ anymore,’’ Allen said. “Now we really have the people in place to make that difference.”

Groups offering support

Nationally, the picture is similar: More women than ever are stepping up to run in 2018, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University-Camden.

The number of women running for the U.S. House of Representatives this year is predicted to be double what it was three years ago. Most of those women are Democrats challenging incumbents, said Kelly Dittmar, assistant professor of political science at Rutgers, who conducts broad national research on women in politics.

Historically, Democrats have elected more women to public office than the GOP; according to research by the center, women account for about 33 percent of elected Democrats, and 10 percent of elected Republicans.

Dittmar said the gains for women have been uneven in terms of geography and race. And the percentage of women in politics is still far below the general population.

“Women are doing better in some places than in other places in the country, and, even in Congress, the rise of women is slow and incremental,’’ Dittmar said. “We still have only six women governors, ” she added, noting that women make up less than 25 percent of “every level of elected leadership, so we have a ways to go to get to gender parity.”

Statewide, women of color still only account for about 9 percent of women elected to office, Allen said.

That number is expected to grow as nonprofit groups recruit, train and support more women candidates and as activist communities, formed around issues, give women more opportunities to lead and support other women.

Sarah Evelyn Myhre, a University of Washington climate researcher, falls into the latter category. She actively supports women candidates, and would run for office if she felt that was where she could have the greatest impact.

Myhre said she feels her personal and professional life is under attack in the Trump administration, which has withdrawn from an international climate accord, staffed federal agencies with people antagonistic to science and cut back women’s health programs, among other things.

It woke her up, she said, to the plight of others who have long been discriminated against. She is now working to build ties to those communities to fight what she sees as an existential threat.

“Whether I’m going to run or whether I’m going to help women run, all of that is in service to the same thing,’’ she said. “My son turned 4 on Halloween. I am so deeply committed to the future of this city and this state, my son’s future. I want to do work that is meaningful and important, and this is the time. This is what my life purpose is about. All these doors that are opening are doors I want to walk through.”

If she decides to run, organizations are ready to help her.

Emerge Washington launched its first 70-hour training program on Friday to train and support women drawn into the public arena to oppose the Trump agenda. The group reports that nearly 40 percent of the women in the program are women of color. Ranging in age from 29 to 68, they are running for city and county councils, school boards and the state Legislature, according to the group.

Another organization, Higher Heights for America, offers training and support for African-American women, while the Richard G. Lugar Excellence in Public Service series aims to draw more women into Republican leadership.

And then there’s EMILY’s List, the fundraising powerhouse for women who support abortion rights. The group reports that nearly 26,000 women — and growing numbers of women of color — have contacted it since November 2016 to express an interest in running for public office.

The state GOP doesn’t have any special programs that recruit women, but actively searches for people who stand out as leaders, said Susan Hutchison, the outgoing chair of the Washington State Republican Party.

“We just look for the best candidate for the job, and an awful lot of them are women,’’ Hutchison said. “It’s not a new thing to have women running for office.”

‘Achievement over ego’

Allen said women take, on average, two-and-a-half years to decide whether to run. But that appears to be changing, she said.

Research shows that women are more likely than men to take family responsibilities into consideration when deciding to run, are more likely to see themselves as less qualified, regardless of their credentials, and are less likely than men to receive encouragement to run.

Dittmar’s research shows that women need that encouragement, that they often are drawn to the public arena by an issue they care about deeply, and realize, at some point, that they can effect the most change if they’re at the table.

How much Hadfield, the new Roslyn City Council member, and other women in office can move the needle on public policy remains to be seen. But research shows their presence makes a difference.

On average, women legislators sponsor and co-sponsor more legislation than men, including legislation on issues affecting women, children and families.

“Women can have a significant influence even when they’re in small numbers,’’ said Dittmar, one of the nation’s leading authorities on the subject. The greater their seniority in office, particularly in Congress, the greater their influence, she said.

Quantifying that influence to show the explicit differences associated with gender is difficult, as usual measures such as bills passed don’t completely capture accomplishments.

To go deeper, Dittmar and her colleagues at the Rutgers center interviewed 83 of the 108 women serving in the 114th Congress. Over 18 months, they pulled women from both sides of the aisle, including Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., and Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Spokane, to discuss whether they were able to make a difference.

The researchers found that “large numbers of congresswomen express the belief that women are more consensual and collaborative than their male colleagues.” They also believed that “women are more results-oriented, more likely to emphasize achievement over ego, and more concerned with achieving policy outcomes rather than receiving publicity or credit.”

In the report “Representation Matters: Women in the U.S. Congress,” Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, said that women congressional leaders “help the legislation move more quickly because of their more collaborative style … In the last Congress, Patty Murray and I led the Housing and Transportation Appropriations Subcommittee; we always produced the bill. Always. Even though we didn’t agree on every issue, we would work together to achieve consensus.”

McMorris Rodgers said she believes that “women are maybe less motivated by what might be next on the career ladder versus actually wanting to make a difference, wanting to make an impact over the long term.”

The report’s authors note, “Most women in Congress take great pride in being female in a male-dominated institution and recognize that their presence is symbolically and substantively important to other women — a sentiment that transcends partisan, ideological, racial/ethnic and chamber differences.”

Correction: Information in this article, originally published Jan. 14, 2018, was corrected Jan. 15, 2018. In a previous version of this story, Kelly Dittmar, the Rutgers professor, noted that nationally, women make up less than 20 percent of “every level of elected leadership” She later said she meant less than 25 percent.